is betteridge's law of headlines correct?

Betteridge’s law of headlines famously asserts that any headline that end in a question mark can be answered by the word “no”. This “law” is of course no law – creating a counter-example is trivial – but should rather be seen as a tongue-in-cheek remark on how poor journalism sometimes hides behind dubious headlines.

In this post we’ll try to answer to what extent Betteridge’s law applies to current articles on the internet. Using the scripts in this repository, we have crawled 13 separate news sites for a total of 26000 headlines (2000 per site) and tried to answer the 766 of them that end in question mark.

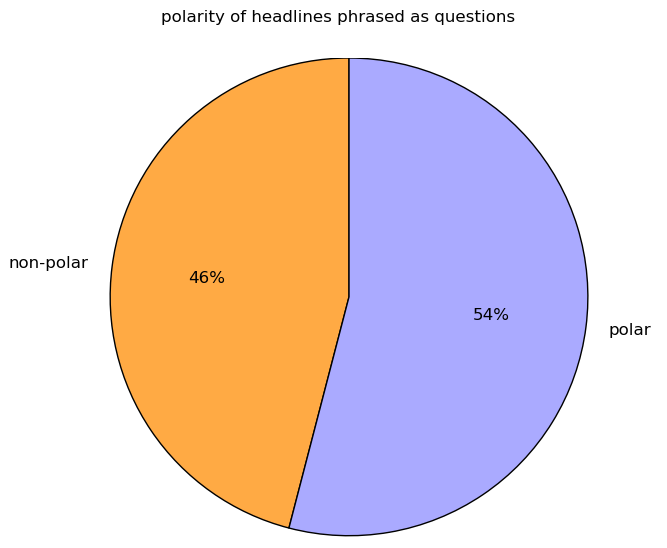

Headline polarity

A polar question is a question for which the expected answer is either “yes” or “no”. We find plenty of these among our 766 headlines, but also plenty of non-polar questions.

For instance, the BBC asks why we value gold and USA Today asks what Facebook could have bought instead of acquiring WhatsApp for $16 billion. We can with confidence rule out both “yes” and “no” as valid answers to these questions, since neither answer makes any sense.

Roughly 46% of the 766 headlines ending in question mark are non-polar. They are not yes-no questions, so the answer can’t be “no”. As such, they contradict Betteridge’s law.

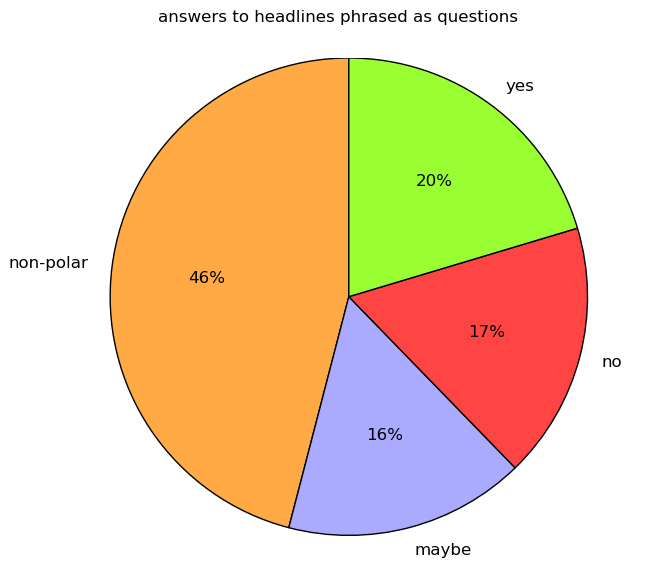

Yes and no but also maybe

Even though Betteridge’s law clearly doesn’t hold for all headlines, could it be that the remaining 54% all have the answer “no”, thereby making the law mostly correct? We did another sweep through the polar headlines to find out.

Answering these headlines is not always simple. For instance, we believe that crunching big data can help feed the world, but disagree that shake shack makes the world’s best burger. These questions are subjective and some may disagree with our answers.

There are also a number of headlines that we failed to answer. For instance, the BBC asks if India is the next university superpower but does not define what “university superpower” means. It doesn’t seem impossible that India could become that, whatever it is, but we can’t really say if it’s more likely to happen than not. Hence, the answer to this, and to several other questions, will have to be “maybe”.

Among the “maybes” there’s a whole plethora of reasons why a clear “yes” or “no” wasn’t provided. In some cases, like above, we doubt anyone can really say. In other cases the answer is probably out there somewhere, but we failed to find it. And there are of course also various sports related questions that we couldn’t muster up the energy to research properly. Interested readers can check out the raw data set for a closer look.

With 46% non-polar and 20% answered “yes”, at least two thirds of our headline sample violates Betteridge’s law. We conclude that it cannot be “mostly correct” either.

Conclusion

We’re going to go out on a limb here and guesstimate that the remaining “maybe” answers can, given enough time and effort, be turned into “yes” or “no” answers, and that these will be distributed similarly to the 20:17 ratio of the fully answered headlines. That would put the total ratio of “no” at 25%.

In other words, it appears as if roughly a quarter of all headlines which end in a question mark can be answered by the word no. You can go ahead and call that Linander’s law of headlines, if you will.

See also: Comments on hacker news